Over the next few months, we’ll be featuring a series on colic. What is it? What causes it? Can you prevent it? What are the different kinds of colic? How much does treatment cost? What are the most common colics we see here in Colorado? We’ll be answering these questions, and many more, so whether you’re an old hand at dealing with colic, or not really sure what it is, you’ll want to read these and familiarize yourself with this very common horse problem.

Today, we’ll discuss some causes of colic, the difference between medical and surgical colic, and basic horse GI anatomy.

There are some horse people who have been involved with horses for many years and have been lucky enough to not have to deal with a colicky horse, but that number is small and the truth is there are two categories of horses – those that have colicked, and those that will colic. Eventually, colic will affect anyone involved with horses.

A colic episode can run the range of severity. The obvious cases of a horse up and down, kicking, pawing, and rolling are easy to recognize. The tougher ones are the ones who may not be eating normally (or at all), may be posturing to urinate (and not urinating), perhaps yawning or stretching their jaw. Just like people, not all horses exhibit discomfort the same. Knowing your horse and his or her habits is the key to early recognition and treatment.

Why Horses Colic

At the most basic level, ‘colic’ is a catch-all term for a belly-ache. The trick is to figure out what’s causing the belly-ache. Remember, horses can’t vomit. Everything that goes in the mouth can only come out the back end, so if a horse has a blockage (impaction), or a twisted or flipped intestine or colon (torsion), feed and gas back up and cause colic.

Causes of colic are myriad, and include:

- Eating something that ferments and produces a lot of painful gas

- Eating a poisonous or otherwise inedible plant

- Stress

- Stomach ulcers

- Change in weather

- Heavy worm load

- Not drinking enough water, causing feed to ball up in a dry lump and block the intestines (an impaction).

- Overeating of normal feeds (grass, hay, alfalfa, grain, etc)

- Sand

- Pedunculated Lipoma (older horses)

- Abrupt changes in feed

- NSAID use (Bute/Banamine)- leading to ulcers

- Idiopathic (unknown) displacement/ torsions

- Infectious (clostridium, salmonella)

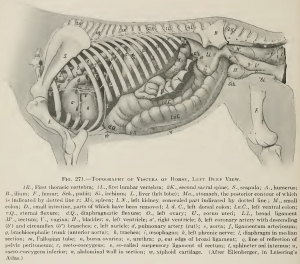

Basic GI Anatomy

A horse is what is called a hindgut fermenter. Unlike a ruminant (cow), which has a large stomach where fermentation (bacterial breakdown) of feed occurs, horses ferment in their colon. The colon of the horse is a large structure that passes 4 times through the abdomen. The design flaw is in how it is attached. This large structure hangs from the top of the body cavity, which can allow the colon (full of gas, liquid and digestive matter), to flip, turn twist and generally move around.

There are several places in a horses’ gut with narrow passages and sharp turns where feed can get stuck, impeding the normal movement of gas and fluid.

A change in the flow of materials through this large fermentation vat (which creates gas), can quickly lead to a buildup of gas in the colon, and this buildup causes a stretch, when leads to pain. A change in the flow of the digesta could also lead to an impaction of feed materials, which again causes a stretching and discomfort to the horse.

Surgical vs Medical Cases

Medical

In our practice, by far most of the colics we see are what we term “medical.” This means that through medication, good management and a bit of time, we can get them through the issue and back to full health.

Pain medication is almost always necessary to make the horse more comfortable. Depending on the level of pain the horse is experiencing, sedation may be needed as well, providing a different level of pain relief. Nasogastric tubing aides the veterinarian in trying to diagnose the reason for the colic, and is also an avenue to administer medications (Mineral oil, electrolytes).

Intestinal lubrication and laxatives can help the blockage to move along and pass. Hydration is vital, so administration of fluids may be warranted. In the field, IV administration of fluids is difficult at best and impossible in most situations. In a medical colic, managed in the field, the best medicine is when the patient decides they should start drinking, because a horse that is drinking, is in all likelihood a hungry horse, and that is NORMAL!

Surgical

When a colic is referred to as “surgical”, it means that the best (and, most of the time, only) way to fix it is through surgery because there is a blockage of some kind that will not resolve itself. For example, the “displacement” or “twisting” of the intestine mentioned above, tumors, enteroliths (intestinal ‘stones’) or other blockages that don’t, or won’t, respond to medical intervention.

These types of colics are very painful. A horse in this situation becomes unaware of their surroundings and is consumed with pain, with or without medication. The heart rate is significantly increased and usually the respiratory rate is as well, and the horse doesn’t respond to pain medication or other methods that typically provide relief.

Next time, we’ll go over some discussion of costs that can be associated with colic, and ways that you can be prepared as horse owners to deal with colic.