Be it in the show ring or over dinner with horse friends, the topic of gastric ulcers always seems to elicit sentiments of frustration and misunderstanding. What causes these pesky ulcers and what can we do as horseman to combat them?

To start, it’s important to understand that before horses were domesticated by humans, they spent their days slowly grazing across the plains and grasslands. The slow ingestion of fibrous plant products creates an integral part of the horse’s digestive mechanism called a fiber mat, which naturally floats on the top of the stomach contents.

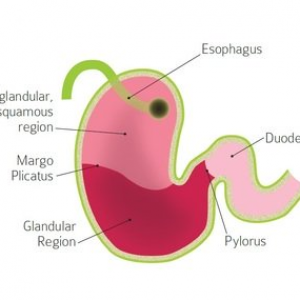

Why is this fiber mat so important? The horse’s stomach is separated into two regions, glandular and non-glandular. The glandular region is responsible for the production of gastric acid which is necessary for the digestion of forage. To avoid self-destruction, the glandular region of the horse’s stomach has protective mechanisms that keep the gastric acid from digesting the very tissue that produces it. Unfortunately, the non-glandular region does not possess such protection and is susceptible to the destructive effects of the acidic stomach contents. This is where the fiber mat comes into play. Horses that graze throughout the course of the day are continuously adding plant fiber to the fiber mat which serves as a protective boundary between the acidic gastric contents and the non-glandular portion of the stomach.

Let’s jump ahead to our typical domesticated horse which lives in a commercial boarding situation. These horses are usually fed twice a day, often going more than twelve hours between their evening meal and breakfast. The detriment here is without the continual ingestion of hay, that fiber mat is quickly digested and sent past the stomach into the rest of the GI tract. This leaves the non-glandular portion of the stomach exposed and susceptible to the deleterious effects of the acidic stomach juices, as these secretions are produced on a continual basis. Now, let’s say we decide to ride this horse without his fiber mat and the increased activity level causes more splashing of the stomach contents onto that already sensitive region. As the acid begins to eat away at the lining of the non-glandular region of the stomach, the horse is thrown into a downward spiraling scenario that, without medical intervention, is quite difficult to recover from.

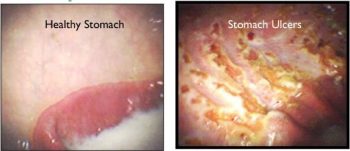

How do you know if your horse has ulcers? Common clinical signs of a horse with ulcers are aversion to tightening of the girth, sensitivity to grooming (especially behind the elbows), finicky eating habits or changes in behavior both on the ground or under saddle. The only guaranteed diagnostic method to confirm the presence and severity of gastric ulcers is by passing an endoscope into the horse’s stomach and visualizing the integrity of the gastric mucosal lining. For many of our clients, this is not a viable diagnostic mechanism, so instead, we assess the horse’s response to medical therapy for ulcers. If there is a vast improvement in clinical signs over the course of therapy, the likelihood of gastric ulceration is high and we can continue with medical intervention and nutritional management.