Colic: Separating Myth from Truth

Every horse owner fears colic, and with good reason: it’s the leading cause of death in horses, aside from old age. Fortunately, a vast majority of colic cases resolve relatively quickly and without surgical intervention. Early recognition of potential issues and knowing what is normal for your horse is crucial. Take the opportunity to assess your horse’s vital signs when he’s healthy so that you can provide your veterinarian with vital information during an emergency. Practice taking his temperature, pulse, and respiratory rate. Listed below are some commonly encountered colic myths.

Myth 1: Casual rolling will cause your horse’s intestine to twist.

If this statement were true, any healthy horse enjoying a good roll in the pasture would be at immediate risk of colicking. Severe pain, such as that associated with a twisted portion of the intestinal tract, will cause a horse to roll repeatedly and violently. If there is a large gas accumulation within a portion of the GI tract, rolling could potentially allow a GI structure to move in/out of its correct position. If your horse is violently colicking, remember to keep yourself safe first. If you can safely prevent your horse from rolling while waiting for veterinary care, please do so.

Myth 2: Always walk a colicking horse.

A mild colic may respond well to a short walking session of 10-15 minutes. But if your horse’s discomfort does not improve or worsens, walking your horse for hours until the point of exhaustion is unlikely to be of benefit to either of you. A horse that is willing to rest or lie down quietly in the same position is fine to remain that way while waiting for your veterinarian to arrive. If your horse is mildly or intermittently uncomfortable and is both willing and safe to walk, a short hand-walk while waiting for your veterinarian is appropriate.

Myth 3: Mineral oil is the best treatment for colic.

Historically mineral oil was the treatment of choice to administer to colics by nasogastric tube, the thought being that the oil would provide a laxative effect for breaking up impacted fecal material. However, a simple experiment can disprove this theory: Place a fecal ball in a cup of mineral oil and place another fecal ball in a cup of warm water and electrolytes. The fecal ball in the warm water/electrolyte solution will soften and break down much more quickly than the fecal ball in oil. Mineral oil is useful as a marker to indicate that manure has passed through the entirety of the gastrointestinal tract and has a useful role in certain types of colic, but its administration is not essential for resolution of most colic cases.

Myth 4: A horse does not have a serious colic if he is passing manure.

Because the gastrointestinal tract of the horse is so long, it is possible to have an obstruction or other issue farther forward in the gastrointestinal tract, with formed manure behind it. In this case, a horse may continue to pass additional manure while still exhibiting signs of colic.

Myth 5: Drastic weather changes cause colic.

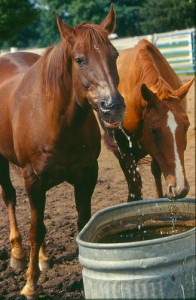

Evidence that weather changes directly cause colic is lacking, but drastic weather changes often alter the management of a horse, which does affect colic risk. For example, keeping horses stalled instead of turning out because of inclement weather is a change in stabling, which is associated with increased colic risk. A sudden drop in temperature may cause a horse’s water source to freeze, which decreases his water intake and increases risk of colic.

Myth 6: Repeatedly posturing to urinate is a sign of a urinary tract problem, not colic.

While urinary issues do occur in horses, colic is much more common. A horse that is seen repeatedly posturing to urinate may be trying to relieve abdominal pain associated with colic.

While it is not possible to prevent every colic, good management strategies can minimize your horse’s risk of colic. Always provide access to clean, non-frozen water. Avoid sudden changes in feed- gradually mix in new concentrates or hay. Maintain a current relationship with your veterinarian to ensure your vet knows your horse and can provide care when the inevitable emergency arises.