EGUS Series Part 3: Management of the horse with Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS)

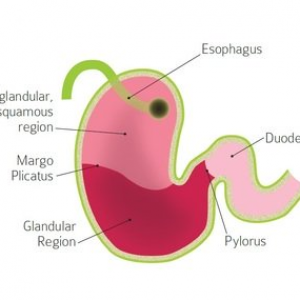

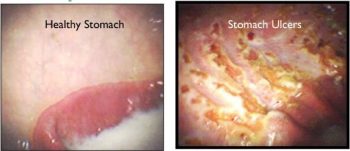

So, we now know how to recognize horses afflicted with EGUS and also the proven therapeutic methods used to treat such horses. This begs the question, how do we manage these ulcer patients? Numerous studies have shown that intense training and competition schedules, frequent shipping, high concentrate (starch) diets, decreased availability of pasture and insufficient ingestion of hay are all common contributing factors to the development of EGUS. Our goals as veterinary professionals are multifaceted and include neutralization of acid, promotion of mucosal repair, and the improvement of management processes.

Knowing that the equine stomach produces 1.5L of acidic stomach juices on an hourly basis, we can already begin to recognize the benefits of having a constant input of hay into the horse’s GI tract. Additionally, if your horse can handle some alfalfa in his diet, there are several benefits to ingesting this leafy legume. When compared to timothy, brome and orchard grass, alfalfa is higher in calcium and protein, both of which act as literal chemical buffers to stomach acid. Additionally, if we consider that alfalfa often has a coarser texture, this means the horse is required to take more chews before swallowing the feed. As the horse masticates, he produces saliva. This gooey substance is high in bicarbonate, a chemically basic molecule which also aids in the neutralization of stomach acid. If your horse is an easy keeper or has some metabolic/nutritional restrictions, high quality straw can also be incorporated into the horse’s forage regime to provide valuable roughage without adding starch or calories.

Why do we avoid diets high in starch? As starch is broken down in the stomach, it is fermented by the resident bacteria into volatile fatty acids and lactic acids, all of which contribute to the already acidic environment of the stomach. If your horse is in an intensive training program and consuming large amounts of grain, breaking the total volume of grain into multiple small feedings throughout the day will help to reduce the amount of acid produced at the time of ingestion. Additionally, fats can be substituted for starches in the form of rice bran, bean meal, and oils as a means to provide calories without the detrimental by-products of starch fermentation.

In addition to the continuous ingestion of fiber products, care should also be taken to reduce the stresses of competition and travel. For those equine athletes where the stresses of competition are unavoidable, the use of PPIs or H2 blockers to prevent the development of gastric ulcers is highly recommended. Finally, while there is no direct link today between the use of probiotics and the prevention of gastric ulcers, such products may be helpful in maintaining hindgut health in stressed equines.

Other ulcer-inducing risk factors in an equine life may include aggressive pasture/stall mates, lack of turnout, consistent loud noises, persistent radios, systemic illness, chronic pain, long term use of NSAIDs (bute, banamine, etc), intensive breeding programs and routine training on an empty stomach.

In conclusion, EGUS is a clinical condition requiring both medical and long term nutritional management. The continuous ingestion of fiber products is by far one of the most important aspects to managing a horse with clinical signs of ulcers, and in achieving long term optimal GI health.