Orthobiologics… say what?!?!?

If you’ve ever had to deal with lameness issues in your horse, you’ve probably heard us use a buffet of acronyms like IRAP and PRP as we discuss the multitude of intraarticular (ie. in the joint) treatment options available in equine sports medicine today. Both IRAP (interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein) and PRP (platelet rich plasma) are considered orthobiologics as these products are harvested from the horse’s own physiologic resources. Other orthobiologics like stem calls are obtained from bone marrow and adipose tissue (fat). Regardless of their origin, these products have been well researched in both equine and human athletes and are now being utilized much more regularly in field ambulatory settings. In this blog, we will review the different types of orthobiologics currently being used in equine medicine and how they compare to the traditional intraarticular steroid therapy.

IRAP (Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Protein)

IRAP is a protein harvested from the horse’s blood. It is incubated and processed over an eight-hour period and then reinjected back into the joint at a later date. It works by permanently binding to the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor which in turn, inhibits the inflammatory pathway within the joint environment. With IRAP permanently bound to the IL-1 receptor, the IL-1 cytokine cannot initiate inflammation in the joint which in turn makes the horse more comfortable and gives the lining of the joint (aka. synovium) the chance to heal. The more opportunity the synovium has to heal in the absence of inflammation, the lower the risk of subsequent development or perpetuation of arthritis.

The benefit with IRAP is that it specifically targets the inflammatory pathway within the joint. It is an extremely specific approach to increasing a horse’s comfort from arthritis, but, it only lasts as long as that deactivated receptor remains intact within the synovium. Once the body naturally metabolizes and overturns the deactivated IL-1 receptor, a new, active IL-1 receptor becomes present in the joint. As a result, horses benefiting from IRAP therapy often require more frequent injections to remain comfortable. Additionally, the initial series of intraarticular IRAP requires two to three injections into the joint, two the three weeks apart. IRAP is labor intensive compared to other autologous products or steroids, but it is extremely effective in decreasing pain and discomfort associated with arthritis and synovitis in equine joints.

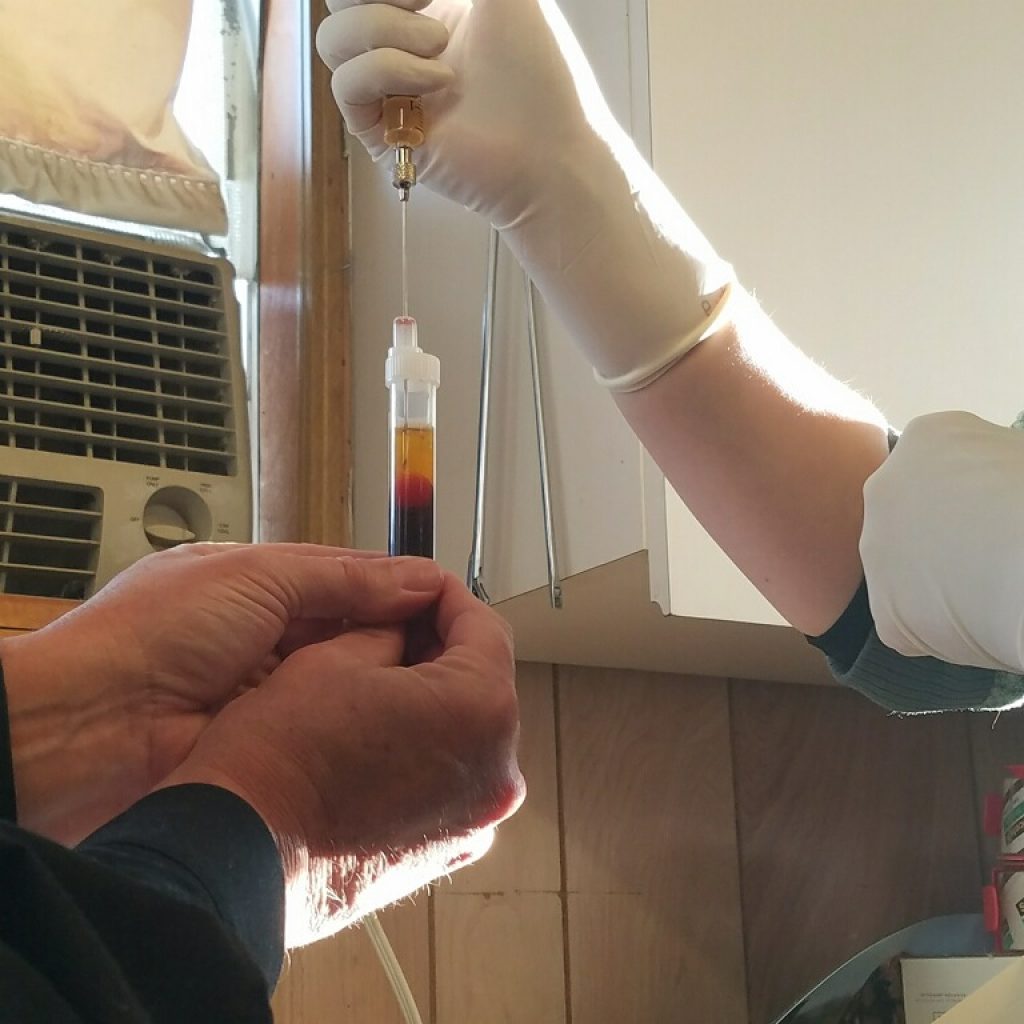

PRP (Platelet Rich Plasma)

PRP is defined as plasma with a higher concentration of platelets compared to whole blood. There are a multitude of factors that can impact the quality of the PRP harvested from a patient, the biggest one being the presence of systemic NSIADs. As a result, we will always ask you to pull your horse off Equioxx/Previcoxx, bute, aspirin or banamine prior to collecting PRP. Once collected from the patient, the blood that will be used in procuring PRP is spun in a centrifuge and the resulting isolated plasma is collected and injected back into the joint or soft tissue structure at the same appointment as the initial blood draw. The therapeutic effect of PRP is due to the presence of a wide variety of growth factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines that decrease inflammation and oxidative stress in the synovium. When used in joints with moderate to severe damage to the cartilage, PRP is thought to help repair the tissue comprising the cartilage to a small extent. Repeat injections can be performed at 3–4-week intervals but the need for multiple injections is not as necessary as in IRAP. Whereas IRAP targets a specific inflammatory pathway, PRP provides a generalized collection of positive, beneficial effects on the joint environment with the intent of reducing inflammation and preserving the synovium. When used in soft tissue injuries, the presence of numerous growth factors in PRP helps to stimulate the development of a stronger matrix for healing as well as the recruitment of proteins for the regeneration of individual cell lines. In doing so, the goal is to encourage a stronger repair than the scar tissue the body normally uses to fill the lesion in the absence of external influence.

Prostride

Prostride is essentially a combination of the physiologic effects of IRAP and PRP. There are a few additional components found within the preparation of Prostride that result in a higher likelihood of joint flares after injection. As such, this is not a product commonly used in our practice, but it is widely researched and utilized in the equine veterinary community.

Stem Cells

Stem cells can be harvested from both the fat and bone marrow of a horse. They are most commonly utilized as part of the therapeutic rehabilitation of soft tissue injuries. One of the biggest issues currently faced in horses with tendon and ligament injuries is the inability to control or direct the cell-type that the body uses to repair a soft tissue lesion. As a result, without intervention, horses commonly lay down scar tissue instead of type I collagen, which is the main component of healthy soft tissue structures. As a result, the repaired structure is usually weaker than the original and prone to a higher rate of reinjury. The purpose of using stem cells is to specifically direct the body to develop and utilize type I collagen when repairing damage to tendons and ligaments. The stem cell research as it pertains to equine medicine is still in its early stages of development but every year more is known about the biochemical and physiologic factors that influence soft tissue repair.

If you have any questions about orthobiologics, as always please reach out to us and we’ll be happy to discuss the options for your horse.